clippings on eco issues, eco friendly life, renewable energy and similar others by dewi darmawati

Friday, 23 December 2016

Monday, 24 October 2016

Friday, 21 October 2016

Monday, 10 October 2016

Friday, 7 October 2016

Tuesday, 20 September 2016

Monday, 19 September 2016

Sunday, 18 September 2016

Obama on Climate Change: The Trends Are ‘Terrifying’

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/08/us/politics/obama-climate-change.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=photo-spot-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news&_r=1

By JULIE HIRSCHFELD DAVIS, MARK LANDLER and CORAL DAVENPORT

In an exclusive interview on his legacy, President Obama speaks to The Times’s Mark Landler and Coral Davenport on climate change while visiting Marine Corps Base Hawaii. By A.J. CHAVAR, BEN LAFFIN, MARK LANDLER and CORAL DAVENPORT on Publish Date September 8, 2016. Photo by A.J. Chavar/The New York Times. Watch in Times Video »

MIDWAY ATOLL — Seventy-four years ago, a naval battle off this remote spit of land in the middle of the Pacific Ocean changed the course of World War II. Last week, President Obama flew here to swim with Hawaiian monk seals and draw attention to a quieter war — one he has waged against rising seas, freakish storms, deadly droughts and other symptoms of a planet choking on its own fumes.

Bombs may not be falling. The sound of gunfire does not concentrate the mind. What Mr. Obama has seen instead are the charts and graphs of a warming planet. “And they’re terrifying,” he said in a recent interview in Honolulu.

“What makes climate change difficult is that it is not an instantaneous catastrophic event,” he said. “It’s a slow-moving issue that, on a day-to-day basis, people don’t experience and don’t see.”

Climate change, Mr. Obama often says, is the greatest long-term threat facing the world, as well as a danger already manifesting itself as droughts, storms, heat waves and flooding. More than health care, more than righting a sinking economic ship, more than the historic first of an African-American president, he believes that his efforts to slow the warming of the planet will be the most consequential legacy of his presidency.

During his seven and a half years in office, Mr. Obama said, a majority of Americans have come to believe “that climate change is real, that it’s important and we should do something about it.” He enacted rules to cut planet-heating emissions across much of the United States economy, from cars to coal plants. He was a central broker of the Paris climate agreement, the first accord committing nearly every country to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Air Force One over Midway Atoll, which Mr. Obama visited last week to expand the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument. CreditA.J. Chavar/The New York Times

But while climate change has played to Mr. Obama’s highest ideals — critics would call them messianic impulses — it has also exposed his weaknesses, namely an inability to forge consensus, even within his own party, on a problem that demands a bipartisan response.

He acknowledged that his rallying cry to save the planet had not galvanized Americans. He has been harshly criticized for policies that objectors see as abuses of executive power and far too burdensome for the economy.

That has made Mr. Obama’s record on climate curiously contradictory, marked by historic achievements abroad and frustrating setbacks at home. The threat of global warming inspired Mr. Obama to conduct some of the most masterful diplomacy of his presidency, which has bound the United States into a web of agreements and obligations overseas. Yet his determination to act alone inflamed his opponents, helped polarize the debate on climate change and will carry a significant economic cost.

Mr. Obama chalks up the contradictions both to politics and to the amorphous, unseen nature of the threat.

“It feels like, ‘Meh, we can put this off a little bit,’” he said.

The president spoke in a cottage on a Marine base that overlooks Kaneohe Bay in his home state, Hawaii. Angry waves crashed on the rocks below the house, the sea churned by one of two hurricanes spinning close to the island. Hawaii, as one of Mr. Obama’s climate advisers pointed out, normally does not get back-to-back hurricanes.

“When you see severe environmental strains of one sort or another on cultures, on civilizations, on nations, the byproducts of that are unpredictable and can be very dangerous,” Mr. Obama said. “If the current projections, the current trend lines on a warming planet continue, it is certainly going to be enormously disruptive worldwide.”

‘All Bets Are Off’

Eight years ago, when Mr. Obama ran for president against Senator John McCain of Arizona, both men had essentially the same position on global warming: It is caused by humans, and Congress should enact legislation to cap greenhouse gas emissions and force polluters to buy and trade permits that would slowly lower overall emissions of climate-warming gases.

But in the summer of 2010, a cap-and-trade bill Mr. Obama had tried to push through Congress failed, blocked by senators from both parties.

“One would have hoped for transformational leadership, in the way J.F.K. would have done it,” said Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, the director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany.

A coal-burning power plant in Buchanan County, Va. Mr. Obama has introduced rules that could force hundreds of such plants to close. CreditGeorge Etheredge for The New York Times

That domestic defeat was compounded by failure on the world stage after efforts to enact a highly anticipated United Nations climate change treaty in Copenhagen fell apart in 2009.

By the fall of 2010, Tea Party “super PACs” supported by the billionaire brothers Charles G. and David H. Koch had seized on cap-and-trade as a political weapon, with attacks that helped Republicans take control of the House.

Polls showed that few Americans thought of climate change as a high public policy priority, and the percentage of voters who accepted the reality that it was caused by humans had tumbled.

“There is the notion that there’s something I might have done that would prevent Republicans to deny climate change,” Mr. Obama said. “I guess hypothetically, maybe there was some trick up my sleeve that would have cast a spell on the Republican caucus and changed their minds.”

In fact, some Republicans, including Senator Lamar Alexander of Tennessee, were willing to go forward with a more limited climate bill that would have restricted emissions only from power plants. But the president’s own party would not unify even around that, with Democrats from industrial and coal states digging in against him. Ironically, Mr. Obama would end up with regulations that narrowly target power plant emissions.

“The White House wanted 60 votes on climate, and they weren’t interested in Republican votes,” Mr. Alexander said in an interview. “Now it’s back to power plant only. The lesson here is that if people who want a result would be a little bit more flexible, they might actually get one.”

In defeat, the president appeared cowed. Campaigning against Mitt Romney in 2012, he barely mentioned climate change.

But soon after Election Day, Mr. Obama interrupted a broad discussion with historians about the country’s challenges with a surprising assertion. Douglas Brinkley, a historian who attended the session, recalled, “Out of nowhere, he said, ‘If we don’t do anything on the climate issue, all bets are off.’”

Mr. Obama, who understood that a legislative push would be fruitless, told his advisers to figure out how to enact deep emissions cuts without Congress. They found a way through the Clean Air Act of 1970, which gives the Environmental Protection Agency the authority to issue regulations on dangerous pollutants.

In 2014, Mr. Obama unveiled the first draft of what would become the Clean Power Plan: a set of Clean Air Act rules that could lead to the closing of hundreds of coal-fired power plants.

The move enraged critics, including Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the majority leader, whose state relies heavily on coal.

Another critic, Laurence H. Tribe, likened the rules to “burning the Constitution” — a charge that might have stung, since Mr. Tribe, a liberal constitutional scholar, was a mentor to Mr. Obama at Harvard Law School.

Mr. Obama dismissed the criticism as the voice of Mr. Tribe’s client, Peabody Energy, the nation’s largest coal company, which filed for bankruptcy protection in April. “You know, I love Larry,” he said, but “when it comes to energy issues, Larry has a history of representing fossil fuel industries in big litigation cases.”

The legality of the climate rules is likely to be decided by the Supreme Court, the composition of which depends on the outcome of the presidential election. Deep-pocketed corporations will not give up the legal fight easily, even after a Supreme Court decision, and Republicans in Congress will continue their legislative attacks. If the rules survive, they will almost certainly cost the coal industry thousands of jobs.

“What we owe the remaining people who are making a living mining coal is to be honest with them,” Mr. Obama said, “and to say that, look, the economy is shifting. How we use energy is shifting. That’s going to be true here, but it’s also going to be true internationally.”

Scrutinizing the Science

Few people would have described Mr. Obama as a climate evangelist when he ran for the White House in 2008. While he invoked the rising seas and heating planet to thrill his young supporters, he did not have the long record of climate activism of Al Gore or John Kerry, who is now his secretary of state. Like many things with Mr. Obama, his evolution on climate was essentially an intellectual journey.

Mr. Obama immersed himself in the scientific literature, which left little doubt that the planet was warming at an accelerating rate. “My top science adviser, John Holdren, periodically will issue some chart or report or graph in the morning meetings,” he said, “and they’re terrifying.”

Unusual weather events like the floods that inundated Louisiana last month are occurring more frequently.CreditBryan Tarnowski for The New York Times

The morning Mr. Obama unveiled the final version of the Clean Power Plan last year, he summoned his senior climate adviser, Brian Deese, to the Oval Office. Mr. Deese expected that the president would hand him some last-minute changes to his speech. Instead, he brought up an article in the journal Science on melting permafrost.

The research not only documented faster increases in temperatures, but also drew direct links between fossil fuel emissions and extreme weather.

Mr. Obama scrutinized reports like the 2014 National Climate Assessment, which tied climate change to events like flooding in Miami and longer, hotter heat waves in the Southwest.

“More and more, there are events that are happening that are astoundingly unusual, that knock your socks off, like the flooding in Louisiana,” said Michael Oppenheimer, a professor of geosciences and international affairs at Princeton University. “Those are the kinds of events where it’s becoming possible to draw attribution.”

Benjamin J. Rhodes, one of the president’s closest aides, recalled Mr. Obama talking about “Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed,” Jared Diamond’s 2005 best seller, which explored the environmental changes that wiped out ancient societies like Easter Island and discussed how modern equivalents like climate change and overpopulation could yield the same destruction.

The president’s Pacific roots also came into play. In Honolulu last week, he told a meeting of Pacific Island leaders that few people understood the stakes of climate change better than residents of their part of the planet. Crops are withering in the Marshall Islands, he noted. Kiribati is buying property in another country for the day that its own land vanishes beneath the waves. And villagers in Fiji have been forced from their homes by high seas.

Shifting monsoon patterns in South Asia could affect a billion people who depend on low-lying agriculture, Mr. Obama said in his interview.

“If you have even a portion of those billion people displaced,” he said, “you now have the sorts of refugee crises and potential conflicts that we haven’t seen in our lifetimes.”

“That,” he added, “promises to make life a lot more difficult for our children and grandchildren.”

Joining Forces With China

Mr. Obama and Hillary Clinton never seem to tire of telling the story of Copenhagen: In December 2009, with the climate conference on the verge of failure, the two learned of a meeting of the leaders of Brazil, China, India and South Africa, from which they had been pointedly excluded. Elbowing their way past a Chinese security guard, they crashed the meeting, and over the course of 90 minutes of tense negotiations with the abashed leaders, they extracted an agreement to set goals for lowering emissions.

The Europeans, who had been cut out of the talks, derided the deal as toothless, but Mr. Obama learned from the experience. A global climate accord could not simply be a compact among developed economies, he said. It had to include the major developing economies, even if they resented being held to standards that had never applied to the club of wealthy nations. And any agreement had to be led by the two largest emitters, the United States and China.

Mr. Obama set about persuading President Xi Jinping of China to join the United States in setting ambitious reduction targets for carbon emissions. Tensions were already high over China’s hacking of American companies, and the United States was balking at China’s slow-motion colonization of the South China Sea. A casual, get-acquainted summit meeting between Mr. Obama and Mr. Xi at the Sunnylands estate in California in June 2013 had failed to break the ice.

Mr. Obama with President Xi Jinping of China in California in June 2013. Despite their differences, the two leaders have worked together on landmark agreements to address climate change.CreditChristopher Gregory/The New York Times

But the meeting did produce one headline: an agreement to explore ways to reduce emissions of hydrofluorocarbons, known as HFCs, potent planet-warming chemicals found in refrigerants. In hindsight, it would prove significant. The final international accord on the chemicals is expected to be ratified next month in Rwanda.

“It was a place Obama and Xi found some common ground,” said John D. Podesta, a chief of staff to President Bill Clinton whom Mr. Obama recruited to lead his climate efforts in his second term. (Mr. Podesta is now the chairman of Mrs. Clinton’s presidential campaign.)

Mr. Podesta and Todd Stern, the State Department’s climate envoy, began arduous negotiations with China. They were backed by Mr. Kerry and Mr. Obama, who sent Mr. Xi a letter with a proposal in which the United States would pledge to increase its target for reducing carbon emissions by 2025 if the Chinese pledged to cap and then gradually reduce their emissions.

China had historically resisted such agreements, but the air pollution there had become so bad, Mr. Obama noted, that the most-visited Twitter page in China was the daily air-quality monitor maintained by the United States Embassy in Beijing.

“One of the reasons I think that China was prepared to go further than it had been prepared to go previously,” Mr. Obama said, “is that their overriding concern tends to be political stability. Interestingly, one of their greatest political vulnerabilities is the environment. People who go to Beijing know that it can be hard to breathe.”

The Chinese were also swayed by Mr. Obama’s announcement in 2014 of his regulations to reduce emissions from coal-fired power plants, which gave Mr. Kerry and his team of climate diplomats the leverage they needed in months of meetings with China. On Nov. 11, 2014, after a quiet stroll across a bridge in the Chinese leadership compound beside the Forbidden City, Mr. Xi and Mr. Obama sealed their agreement.

“By locking in China,” Mr. Obama said, “it now allowed me to go to India and South Africa and Brazil and others and say to them: ‘Look, we don’t expect countries with big poverty rates and relatively low per-capita carbon emissions to do exactly the same thing that the United States or Germany or other advanced countries are doing. But you’ve got to do something.’”

A little more than a year later, in Paris, the United States led negotiations among 195 countries that resulted in the most significant climate change agreement in history. And this past weekend in Hangzhou, China, Mr. Obama and Mr. Xi formally committed their two nations to the Paris accord. For Mr. Obama, it was not just redemption for Copenhagen, but a vindication of his theory of the United States’ role in the world.

“There are certain things that the United States can do by itself,” Mr. Obama said. “But if we’re going to actually solve a problem, then our most important role is as a leader, vision setter and convener.”

An Ambitious, Divisive Legacy

To his successor, Mr. Obama leaves an ambitious and divisive legacy: a raft of new emissions rules that promise to transform the United States economy but are likely to draw continuing fire from Republicans, and an aggressive — some say unrealistic — pledge made in Paris to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80 percent from 2005 levels by 2050.

Mr. Obama in a meeting with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey, left, during the climate talks in Paris in December. CreditStephen Crowley/The New York Times

All of this, he acknowledges, could be undone at the ballot box. “I think it’s fair to say that if Donald Trump is elected, for example, you have a pretty big shift now with how the E.P.A. operates,” he said.

Mrs. Clinton has embraced Mr. Obama’s go-it-alone approach, promising to meet and in some cases exceed his goals without trying to pass cap-and-trade legislation. She is proposing marquee projects like installing 500 million solar panels by 2020 and giving states and cities $60 billion to invest in energy-efficient public transportation and buildings.

“It will be first-order business,” Mr. Podesta said.

But Mrs. Clinton will face the same partisan fire Mr. Obama has. He noted that, like him, Mrs. Clinton had been pilloried in coal country for acknowledging that coal mining would have a declining role in a 21st-century economy. Mr. Obama’s bet is that as his regulations get woven into the fabric of the economy, they will be harder for anyone to unwind. He says that his successor should promote past victories, including those of Republicans like Richard M. Nixon and George Bush.

For his part, Mr. Obama said he planned to stay active in fighting climate change in his post-presidential life. During his tour of the wildlife on Midway, he paused to make an improbable remark.

“My hope,” he said, “is that maybe as ex-president I can have a little more influence on some of my Republican friends, who I think up until now have been resistant to the science.”

Julie Hirschfeld Davis reported from Midway Atoll, and Mark Landler and Coral Davenport from Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii.

By JULIE HIRSCHFELD DAVIS, MARK LANDLER and CORAL DAVENPORT

In an exclusive interview on his legacy, President Obama speaks to The Times’s Mark Landler and Coral Davenport on climate change while visiting Marine Corps Base Hawaii. By A.J. CHAVAR, BEN LAFFIN, MARK LANDLER and CORAL DAVENPORT on Publish Date September 8, 2016. Photo by A.J. Chavar/The New York Times. Watch in Times Video »

MIDWAY ATOLL — Seventy-four years ago, a naval battle off this remote spit of land in the middle of the Pacific Ocean changed the course of World War II. Last week, President Obama flew here to swim with Hawaiian monk seals and draw attention to a quieter war — one he has waged against rising seas, freakish storms, deadly droughts and other symptoms of a planet choking on its own fumes.

Bombs may not be falling. The sound of gunfire does not concentrate the mind. What Mr. Obama has seen instead are the charts and graphs of a warming planet. “And they’re terrifying,” he said in a recent interview in Honolulu.

“What makes climate change difficult is that it is not an instantaneous catastrophic event,” he said. “It’s a slow-moving issue that, on a day-to-day basis, people don’t experience and don’t see.”

Climate change, Mr. Obama often says, is the greatest long-term threat facing the world, as well as a danger already manifesting itself as droughts, storms, heat waves and flooding. More than health care, more than righting a sinking economic ship, more than the historic first of an African-American president, he believes that his efforts to slow the warming of the planet will be the most consequential legacy of his presidency.

During his seven and a half years in office, Mr. Obama said, a majority of Americans have come to believe “that climate change is real, that it’s important and we should do something about it.” He enacted rules to cut planet-heating emissions across much of the United States economy, from cars to coal plants. He was a central broker of the Paris climate agreement, the first accord committing nearly every country to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Air Force One over Midway Atoll, which Mr. Obama visited last week to expand the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument. CreditA.J. Chavar/The New York Times

But while climate change has played to Mr. Obama’s highest ideals — critics would call them messianic impulses — it has also exposed his weaknesses, namely an inability to forge consensus, even within his own party, on a problem that demands a bipartisan response.

He acknowledged that his rallying cry to save the planet had not galvanized Americans. He has been harshly criticized for policies that objectors see as abuses of executive power and far too burdensome for the economy.

That has made Mr. Obama’s record on climate curiously contradictory, marked by historic achievements abroad and frustrating setbacks at home. The threat of global warming inspired Mr. Obama to conduct some of the most masterful diplomacy of his presidency, which has bound the United States into a web of agreements and obligations overseas. Yet his determination to act alone inflamed his opponents, helped polarize the debate on climate change and will carry a significant economic cost.

Mr. Obama chalks up the contradictions both to politics and to the amorphous, unseen nature of the threat.

“It feels like, ‘Meh, we can put this off a little bit,’” he said.

The president spoke in a cottage on a Marine base that overlooks Kaneohe Bay in his home state, Hawaii. Angry waves crashed on the rocks below the house, the sea churned by one of two hurricanes spinning close to the island. Hawaii, as one of Mr. Obama’s climate advisers pointed out, normally does not get back-to-back hurricanes.

“When you see severe environmental strains of one sort or another on cultures, on civilizations, on nations, the byproducts of that are unpredictable and can be very dangerous,” Mr. Obama said. “If the current projections, the current trend lines on a warming planet continue, it is certainly going to be enormously disruptive worldwide.”

‘All Bets Are Off’

Eight years ago, when Mr. Obama ran for president against Senator John McCain of Arizona, both men had essentially the same position on global warming: It is caused by humans, and Congress should enact legislation to cap greenhouse gas emissions and force polluters to buy and trade permits that would slowly lower overall emissions of climate-warming gases.

But in the summer of 2010, a cap-and-trade bill Mr. Obama had tried to push through Congress failed, blocked by senators from both parties.

“One would have hoped for transformational leadership, in the way J.F.K. would have done it,” said Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, the director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany.

A coal-burning power plant in Buchanan County, Va. Mr. Obama has introduced rules that could force hundreds of such plants to close. CreditGeorge Etheredge for The New York Times

That domestic defeat was compounded by failure on the world stage after efforts to enact a highly anticipated United Nations climate change treaty in Copenhagen fell apart in 2009.

By the fall of 2010, Tea Party “super PACs” supported by the billionaire brothers Charles G. and David H. Koch had seized on cap-and-trade as a political weapon, with attacks that helped Republicans take control of the House.

Polls showed that few Americans thought of climate change as a high public policy priority, and the percentage of voters who accepted the reality that it was caused by humans had tumbled.

“There is the notion that there’s something I might have done that would prevent Republicans to deny climate change,” Mr. Obama said. “I guess hypothetically, maybe there was some trick up my sleeve that would have cast a spell on the Republican caucus and changed their minds.”

In fact, some Republicans, including Senator Lamar Alexander of Tennessee, were willing to go forward with a more limited climate bill that would have restricted emissions only from power plants. But the president’s own party would not unify even around that, with Democrats from industrial and coal states digging in against him. Ironically, Mr. Obama would end up with regulations that narrowly target power plant emissions.

“The White House wanted 60 votes on climate, and they weren’t interested in Republican votes,” Mr. Alexander said in an interview. “Now it’s back to power plant only. The lesson here is that if people who want a result would be a little bit more flexible, they might actually get one.”

In defeat, the president appeared cowed. Campaigning against Mitt Romney in 2012, he barely mentioned climate change.

But soon after Election Day, Mr. Obama interrupted a broad discussion with historians about the country’s challenges with a surprising assertion. Douglas Brinkley, a historian who attended the session, recalled, “Out of nowhere, he said, ‘If we don’t do anything on the climate issue, all bets are off.’”

Mr. Obama, who understood that a legislative push would be fruitless, told his advisers to figure out how to enact deep emissions cuts without Congress. They found a way through the Clean Air Act of 1970, which gives the Environmental Protection Agency the authority to issue regulations on dangerous pollutants.

In 2014, Mr. Obama unveiled the first draft of what would become the Clean Power Plan: a set of Clean Air Act rules that could lead to the closing of hundreds of coal-fired power plants.

The move enraged critics, including Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the majority leader, whose state relies heavily on coal.

Another critic, Laurence H. Tribe, likened the rules to “burning the Constitution” — a charge that might have stung, since Mr. Tribe, a liberal constitutional scholar, was a mentor to Mr. Obama at Harvard Law School.

Mr. Obama dismissed the criticism as the voice of Mr. Tribe’s client, Peabody Energy, the nation’s largest coal company, which filed for bankruptcy protection in April. “You know, I love Larry,” he said, but “when it comes to energy issues, Larry has a history of representing fossil fuel industries in big litigation cases.”

The legality of the climate rules is likely to be decided by the Supreme Court, the composition of which depends on the outcome of the presidential election. Deep-pocketed corporations will not give up the legal fight easily, even after a Supreme Court decision, and Republicans in Congress will continue their legislative attacks. If the rules survive, they will almost certainly cost the coal industry thousands of jobs.

“What we owe the remaining people who are making a living mining coal is to be honest with them,” Mr. Obama said, “and to say that, look, the economy is shifting. How we use energy is shifting. That’s going to be true here, but it’s also going to be true internationally.”

Scrutinizing the Science

Few people would have described Mr. Obama as a climate evangelist when he ran for the White House in 2008. While he invoked the rising seas and heating planet to thrill his young supporters, he did not have the long record of climate activism of Al Gore or John Kerry, who is now his secretary of state. Like many things with Mr. Obama, his evolution on climate was essentially an intellectual journey.

Mr. Obama immersed himself in the scientific literature, which left little doubt that the planet was warming at an accelerating rate. “My top science adviser, John Holdren, periodically will issue some chart or report or graph in the morning meetings,” he said, “and they’re terrifying.”

Unusual weather events like the floods that inundated Louisiana last month are occurring more frequently.CreditBryan Tarnowski for The New York Times

The morning Mr. Obama unveiled the final version of the Clean Power Plan last year, he summoned his senior climate adviser, Brian Deese, to the Oval Office. Mr. Deese expected that the president would hand him some last-minute changes to his speech. Instead, he brought up an article in the journal Science on melting permafrost.

The research not only documented faster increases in temperatures, but also drew direct links between fossil fuel emissions and extreme weather.

Mr. Obama scrutinized reports like the 2014 National Climate Assessment, which tied climate change to events like flooding in Miami and longer, hotter heat waves in the Southwest.

“More and more, there are events that are happening that are astoundingly unusual, that knock your socks off, like the flooding in Louisiana,” said Michael Oppenheimer, a professor of geosciences and international affairs at Princeton University. “Those are the kinds of events where it’s becoming possible to draw attribution.”

Benjamin J. Rhodes, one of the president’s closest aides, recalled Mr. Obama talking about “Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed,” Jared Diamond’s 2005 best seller, which explored the environmental changes that wiped out ancient societies like Easter Island and discussed how modern equivalents like climate change and overpopulation could yield the same destruction.

The president’s Pacific roots also came into play. In Honolulu last week, he told a meeting of Pacific Island leaders that few people understood the stakes of climate change better than residents of their part of the planet. Crops are withering in the Marshall Islands, he noted. Kiribati is buying property in another country for the day that its own land vanishes beneath the waves. And villagers in Fiji have been forced from their homes by high seas.

Shifting monsoon patterns in South Asia could affect a billion people who depend on low-lying agriculture, Mr. Obama said in his interview.

“If you have even a portion of those billion people displaced,” he said, “you now have the sorts of refugee crises and potential conflicts that we haven’t seen in our lifetimes.”

“That,” he added, “promises to make life a lot more difficult for our children and grandchildren.”

Joining Forces With China

Mr. Obama and Hillary Clinton never seem to tire of telling the story of Copenhagen: In December 2009, with the climate conference on the verge of failure, the two learned of a meeting of the leaders of Brazil, China, India and South Africa, from which they had been pointedly excluded. Elbowing their way past a Chinese security guard, they crashed the meeting, and over the course of 90 minutes of tense negotiations with the abashed leaders, they extracted an agreement to set goals for lowering emissions.

The Europeans, who had been cut out of the talks, derided the deal as toothless, but Mr. Obama learned from the experience. A global climate accord could not simply be a compact among developed economies, he said. It had to include the major developing economies, even if they resented being held to standards that had never applied to the club of wealthy nations. And any agreement had to be led by the two largest emitters, the United States and China.

Mr. Obama set about persuading President Xi Jinping of China to join the United States in setting ambitious reduction targets for carbon emissions. Tensions were already high over China’s hacking of American companies, and the United States was balking at China’s slow-motion colonization of the South China Sea. A casual, get-acquainted summit meeting between Mr. Obama and Mr. Xi at the Sunnylands estate in California in June 2013 had failed to break the ice.

Mr. Obama with President Xi Jinping of China in California in June 2013. Despite their differences, the two leaders have worked together on landmark agreements to address climate change.CreditChristopher Gregory/The New York Times

But the meeting did produce one headline: an agreement to explore ways to reduce emissions of hydrofluorocarbons, known as HFCs, potent planet-warming chemicals found in refrigerants. In hindsight, it would prove significant. The final international accord on the chemicals is expected to be ratified next month in Rwanda.

“It was a place Obama and Xi found some common ground,” said John D. Podesta, a chief of staff to President Bill Clinton whom Mr. Obama recruited to lead his climate efforts in his second term. (Mr. Podesta is now the chairman of Mrs. Clinton’s presidential campaign.)

Mr. Podesta and Todd Stern, the State Department’s climate envoy, began arduous negotiations with China. They were backed by Mr. Kerry and Mr. Obama, who sent Mr. Xi a letter with a proposal in which the United States would pledge to increase its target for reducing carbon emissions by 2025 if the Chinese pledged to cap and then gradually reduce their emissions.

China had historically resisted such agreements, but the air pollution there had become so bad, Mr. Obama noted, that the most-visited Twitter page in China was the daily air-quality monitor maintained by the United States Embassy in Beijing.

“One of the reasons I think that China was prepared to go further than it had been prepared to go previously,” Mr. Obama said, “is that their overriding concern tends to be political stability. Interestingly, one of their greatest political vulnerabilities is the environment. People who go to Beijing know that it can be hard to breathe.”

The Chinese were also swayed by Mr. Obama’s announcement in 2014 of his regulations to reduce emissions from coal-fired power plants, which gave Mr. Kerry and his team of climate diplomats the leverage they needed in months of meetings with China. On Nov. 11, 2014, after a quiet stroll across a bridge in the Chinese leadership compound beside the Forbidden City, Mr. Xi and Mr. Obama sealed their agreement.

“By locking in China,” Mr. Obama said, “it now allowed me to go to India and South Africa and Brazil and others and say to them: ‘Look, we don’t expect countries with big poverty rates and relatively low per-capita carbon emissions to do exactly the same thing that the United States or Germany or other advanced countries are doing. But you’ve got to do something.’”

A little more than a year later, in Paris, the United States led negotiations among 195 countries that resulted in the most significant climate change agreement in history. And this past weekend in Hangzhou, China, Mr. Obama and Mr. Xi formally committed their two nations to the Paris accord. For Mr. Obama, it was not just redemption for Copenhagen, but a vindication of his theory of the United States’ role in the world.

“There are certain things that the United States can do by itself,” Mr. Obama said. “But if we’re going to actually solve a problem, then our most important role is as a leader, vision setter and convener.”

An Ambitious, Divisive Legacy

To his successor, Mr. Obama leaves an ambitious and divisive legacy: a raft of new emissions rules that promise to transform the United States economy but are likely to draw continuing fire from Republicans, and an aggressive — some say unrealistic — pledge made in Paris to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80 percent from 2005 levels by 2050.

Mr. Obama in a meeting with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey, left, during the climate talks in Paris in December. CreditStephen Crowley/The New York Times

All of this, he acknowledges, could be undone at the ballot box. “I think it’s fair to say that if Donald Trump is elected, for example, you have a pretty big shift now with how the E.P.A. operates,” he said.

Mrs. Clinton has embraced Mr. Obama’s go-it-alone approach, promising to meet and in some cases exceed his goals without trying to pass cap-and-trade legislation. She is proposing marquee projects like installing 500 million solar panels by 2020 and giving states and cities $60 billion to invest in energy-efficient public transportation and buildings.

“It will be first-order business,” Mr. Podesta said.

But Mrs. Clinton will face the same partisan fire Mr. Obama has. He noted that, like him, Mrs. Clinton had been pilloried in coal country for acknowledging that coal mining would have a declining role in a 21st-century economy. Mr. Obama’s bet is that as his regulations get woven into the fabric of the economy, they will be harder for anyone to unwind. He says that his successor should promote past victories, including those of Republicans like Richard M. Nixon and George Bush.

For his part, Mr. Obama said he planned to stay active in fighting climate change in his post-presidential life. During his tour of the wildlife on Midway, he paused to make an improbable remark.

“My hope,” he said, “is that maybe as ex-president I can have a little more influence on some of my Republican friends, who I think up until now have been resistant to the science.”

Julie Hirschfeld Davis reported from Midway Atoll, and Mark Landler and Coral Davenport from Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii.

Wednesday, 14 September 2016

Landfills: An Unexpected Source of Renewable Energy

http://real-leaders.com/landfills-an-unexpected-source-of-renewable-energy/

Did you know that the garbage you throw out every day is a source of green energy? The gas naturally generated by landfills fuels vehicles and powers the electric grid, easing our dependence on fossil fuels and foreign oil.

“Landfill gas is a resource the waste and recycling industry is proud to reliably provide 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” says Sharon H. Kneiss, president and CEO of the National Waste & Recycling Association. “It’s renewable energy produced in America.”

How does it work?

Today’s modern landfills are highly engineered facilities run under strict federal and state regulations to ensure protection of human health and the environment.

When trash like grass clippings, banana peels and coffee grinds gets buried beneath a layer of soil in a landfill, it eventually breaks down and produces gas. Landfill operators safely collect this gas by applying a vacuum to collection wells throughout a landfill. The gas is then piped to a compression and filtering unit, where it’s prepared for use by power plants and others.

But how much energy is actually generated?

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, waste-based energy is the source of over 5 percent of America’s renewable energy – and there’s plenty of room to grow. In March 2015, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported that 645 sites had landfill-gas-to-energy programs (in every state except Hawaii and Wyoming). The EPA has identified an additional 440 landfills as expansion candidates.

Landfill operators are also starting to generate energy beyond gas by placing solar panels and windmills on landfills. The power produced can be fed into local electric grids for local homes and businesses.

Today, a landfill is designed from the start to protect the environment and public health. Later, it provides benefits even when it closes. Once a landfill has reached its permitted capacity, it is closed and engineered to keep water out by installing a cap made of clay or a synthetic material. A drainage layer, a protective soil cover and topsoil are then added to support plant growth.

These spaces are transformed into parks, golf courses, wildlife refuges and other places that can be enjoyed by the entire community.

Wednesday, 7 September 2016

Tuesday, 6 September 2016

Saturday, 3 September 2016

Precious plastic: getting started your plastic recycling workshop

Intro:

Plastics:

Build a machine:

Build a shredder:

Build a compressor:

Build an injection molding machine:

Build an extrusion machine:

Collecting Plastic:

Create with plastic:

Browse what others made:

3D Filament maker

Thursday, 18 August 2016

Sunday, 7 August 2016

Monday, 20 June 2016

“Lereng Kritis”, Mengapa Longsor ?

https://rovicky.wordpress.com/2016/06/19/lereng-kritis-mengapa-longsor/

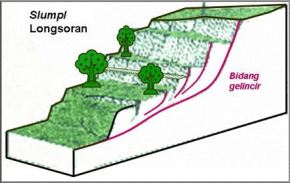

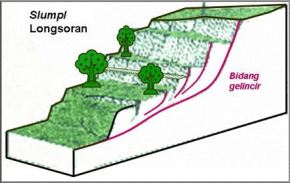

Alam memiliki mekanisme unik. Hampir semua lereng bukit pada saat ini sejatinya pada kondisi kritisnya. Longsor merupakan saat ketika kondisi kritisnya terlampaui oleh sebuah gangguan. Gangguan ini dapat berupa pembebanan baru, atau karena perubahan (pemotongan lereng).

“Wis Pakde, semakin rumit semakin kompleks. malah sulit dimengerti nanti”

“Wis Pakde, semakin rumit semakin kompleks. malah sulit dimengerti nanti”

Alam memiliki mekanisme unik. Hampir semua lereng bukit pada saat ini sejatinya pada kondisi kritisnya. Longsor merupakan saat ketika kondisi kritisnya terlampaui oleh sebuah gangguan. Gangguan ini dapat berupa pembebanan baru, atau karena perubahan (pemotongan lereng).

Salah satu gangguan beban adalah penambahan air oleh hujan dimana saat ini menjadi pemicu uatama beberapa longsor.

Salah satu cara yang mudah untuk mengerti teori longsor adalah dengan membuat sandpileatau tumpukan pasir. Yaitu melihat realitasnya dengan tumpukan pasir atau boleh juga tumpukan beras seperti diatas itu. Nah yang sebelah ini adalah caranya untuk melihat dengan sebuah model.

Buatlah tumpukan beras, kemudian lihatlah seberapa besar lereng maksimumnya. Bila kamu tambah maka butirannya akan jatuh kebawah. Itu artinya sudutnya sudah maksimum.

“Pakde, kalau pakai butiran kacang hujau sudutnya beda ya ?”

Kita coba beberapa modelnya.

Model 1

Model disebelah ini menggambarkan bagaimana sebuah tumpukan kotak biru (anggap saja satu butir pasir) yang akan stabil apabila sudut kelerengannya atau gradiennya 2 atau 60 derajat. Sudut ini akan menjadi sudut kritisnya.

Ketika ditambah satu butir pasir saja tumpukan diatasnya, maka tumpukan itu akan jatuh kebawahnya, dan yang dibawah akan jatuh ke bawahnya lagi, dan seterusnya. Sampai maksimum hanya dua tumpukan disebalah ruang kosong. Ini mirip sebagai analogi, bila ada penambahan beban diatas bukit, atau adanya beban tambahan karena adanya air hujan.

Dengan demikian sudut kritis ini akan selalu terjaga. Dan akan menjadi sudut kritis berikutnya.

Dapat juga gangguan berupa pengambilan dibawahnya yang berakibat sama yaitu jatuhnya butiran diatasnya. Ini mirip kalau ada cutting pemotongan tebing.

“Pakde, kalau begitu kondisi alam selalu dalam kondisi kritis ?”

“Lebih tepatnya, alam itu selalu dinamis. Selalu berubah-ubah. Dan itu cirikhas dari planet yang ‘hidup‘

Model 2

Model berikut ini misal ketika ada material lain disebelahnya, maka sudah mulai terlihat sedikit bertambahkompleks. Menambah dan mengambil satu butir atau satu tumpukan kotak saja sudah akan mempengaruhi kestabilan tebing atau kestabilan lereng.

Aplikasi ini mudah dilakukan kalau anda sebagai petugas gudang ingin menumpuk-numpuk barang. Itulah sebabnya ada tulisan dalam setiap kardus kemasan. Maksimum tumpukannya akan tertulis. Selain ditakutkan akan runtuh tumpukan kotak ini juga bisa jadi tidak kuat menahan beban diatasnya.

Semakin banyak jenis dan ukuran butiran, maka akan semakin rumit juga kalau ingin dibuat model matematisnya.

“Whadooh, makin lama makin rumit pakde”

Namun seringkali, alam memiliki cara mneyelesaikan dengan analogi juga statistik dalam menyelesaikan equation (rumusan).

Model 3

Model ke 3 ini lebih kompleks dan mungkin banyak terdapat di alam ketika ada sebuah tumpuk-tumpukan material penyusun.

Misalnya saja tumpukan batuan. Coba bandingkan gambar ini dan diatas ini. Bagaimana seandainya saya mengambil satu kotak saja. Maka bentuk akhirnya tentu akan berbeda. Secara mudah saja kita akan tahu bagaimana kompleksnya seandainya tumpukan ini bukan hanya tumpukan kardus mie dicampur kardus kopi dan kardus roti. Di alam mungkin batuanpun terdiri dari bermacam-macam ukuran serta jenis materialnya.

Memang melihat contoh, foto, gambar dan analogi sering kali lebih mudah untuk mengenali alam sekitar kita. Itulah sebabnya mengapa ilmu geologi semestinya lebih mudah ketimbang ilmu matematika yang hanya angka abstrak looh.

Dimana bumi dipijak ketahuilah apa dibawah telapak kakimu.

Alam itu sangat beragam, bahkan setiap bukit itu unik, dalam satu gunung juga unik. Pengenalan daerah seringkali lebih tepat. Apabila ada daerah yang barusaja longsor, dan apabila kita dapat merekonstruksikannya, maka mungkin kondisi tepat sebelum longsor dapat dianggap sebagai kondisi kritis. Ini pendekatan sederhananya saja. Dilapangan tentu akan bervariasi. Tetapi pendekatan ini dapat dipakai untuk melokalisir daerah berpotensi longsor.

Kalau kamu melihat gambar disamping, tentunya kamu tahu bahwa matematika itu jauh lebih sulit dari ilmu geologi kan ?

di-copas dari Dongeng Geologi by pak Rovicky https://rovicky.wordpress.com/

di-copas dari Dongeng Geologi by pak Rovicky https://rovicky.wordpress.com/

MENGENALI GEJALA AWAL LONGSOR.

https://rovicky.wordpress.com/2016/06/19/mengenali-gejala-awal-longsor-2/

[Keprihatinan banjir dan longsor yg terjadi di beberapa tempat].

[Keprihatinan banjir dan longsor yg terjadi di beberapa tempat].

Bencana longsor disetiap musim hujan akhir tahun maupun tengah tahun karena pergeseran musim selalu saja mengagetkan dan selalu menunjuk hidung kita sendiri. Ya benar, kita pernah tahu dan kita juga sudah belajar dan kita juga sudah mengantisipasi. Tapi mengapa masih juga menelan korban ?

Mungkin saja masih ada yg terlupa pada program mitigasi kebencanaan kita selama ini. Mungkin kita perlu melihat dari kacamata berbeda

Hujan merupakan pemicu utama bencana longsor, oleh sebab itu maka ketika hujan deras terjadi, perhatikan daerah berlereng tajam, derah kurang vegetasi dan daerah yg banyak dijumpai rekahan/retak. Gejala-gejala dan pemicu longsor ini semestinya dapat lebih mudah dikenali. Namun tidak mungkin semua mengerti gejala dan pemicu ini, sehingga harus dengan koordinasi. Kalau toh koordinasi juga masih sulit salah satu yg paling memungkinkan adalah “berbagi”. Ya, saling berbagi informasi.

Anak-anak desa yang suka berpetualang menjadi “surveyor”.

Retakan terbuka dan relatif lurus di ujung bukit berlereng tajam, sebagai tanda awal longsor.

Mengenali rekahan bukanlah hal yg sulit, anak-anak yg suka berjalan berkelana kesana kemari dapat diajari untuk mengenali gejala ini.

Retakan sebagai gejala awal longsoran biasanya lurus panjang dan terbuka. Kalau anak-anak diajari ttg hal ini, mungkin akan menjadi “agen agen mitigasi” yg handal.

Dan bila mereka melihat gejala itu diminta membertahukan ke guru atau kakaknya bila melihat gejala ini saat ada di jalan pulang sekolah atau saat bermain.

Tips Menghadapi Longsor dan Ciri Daerah Rawan Longsor

Amblesan di lereng yg awalnya beberapa centi akan berkembang menjadi beberapa meter. haris diwaspadai. Khususnya yang tinggal dibawahnya.

Ciri Daerah Rawan Longsor

1. Daerah berbukit dengan kelerengan lebih dari 20 derajat

2. Lapisan tanah tebal di atas lereng

3. Sistem tata air dan tata guna lahan yang kurang baik

4. Lereng terbuka atau gundul

5. Terdapat retakan tapal kuda pada bagian atas tebing

6. Banyaknya mata air/rembesan air pada tebing disertai longsoran-longsoran kecil

7. Adanya aliran sungai di dasar lereng

8. Pembebanan yang berlebihan pada lereng seperti adanya bangunan rumah atau saranan lainnya.

9. Pemotongan tebing untuk pembangunan rumah atau jalan

1. Daerah berbukit dengan kelerengan lebih dari 20 derajat

2. Lapisan tanah tebal di atas lereng

3. Sistem tata air dan tata guna lahan yang kurang baik

4. Lereng terbuka atau gundul

5. Terdapat retakan tapal kuda pada bagian atas tebing

6. Banyaknya mata air/rembesan air pada tebing disertai longsoran-longsoran kecil

7. Adanya aliran sungai di dasar lereng

8. Pembebanan yang berlebihan pada lereng seperti adanya bangunan rumah atau saranan lainnya.

9. Pemotongan tebing untuk pembangunan rumah atau jalan

Upaya mengurangi tanah longsor

1. Menutup retakan pada atas tebing dengan material lempung.

2. Menanami lereng dengan tanaman serta memperbaiki tata air dan guna lahan.

3. Waspada terhadap mata air/rembesan air pada lereng.

4. Waspada padsa saat curah hujan yang tinggi pada waktu yang lama

1. Menutup retakan pada atas tebing dengan material lempung.

2. Menanami lereng dengan tanaman serta memperbaiki tata air dan guna lahan.

3. Waspada terhadap mata air/rembesan air pada lereng.

4. Waspada padsa saat curah hujan yang tinggi pada waktu yang lama

Yang dilakukan pada saat dan setelah longsor

Longsoran kecil-kecil perlu dipetakan untuk melihat besarnya potensi longsor.

1. Karena longsor terjadi pada saat yang mendadak, evakuasi penduduk segera setelah diketahui tanda-tanda tebing akan longsor.

2. Segera hubungi pihak terkait dan lakukan pemindahan korban dengan hati-hati.

3. Segera lakukan pemindahan penduduk ke tempat yang aman.

di-copas dari Dongeng Geologi by pak Rovicky https://rovicky.wordpress.com/

2. Segera hubungi pihak terkait dan lakukan pemindahan korban dengan hati-hati.

3. Segera lakukan pemindahan penduduk ke tempat yang aman.

di-copas dari Dongeng Geologi by pak Rovicky https://rovicky.wordpress.com/

Wednesday, 1 June 2016

Saturday, 23 April 2016

Saturday, 9 April 2016

Renewable Energy

Ocean Waves May Hold The Key To Endless Renewable Energy.This technology turns ocean waves into electrical power and fresh drinking water.

Posted by HuffPost Business on Friday, 1 April 2016

Tuesday, 8 March 2016

PALM OIL: WHO’S STILL TRASHING FORESTS?

http://www.greenpeace.org.au/blog/palm-oil-whos-still-trashing-forests/?utm_content=buffer5b0c7&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer

How ‘clean’ is the palm oil used by major brands around the world? Today, we’re releasing the results of our investigation into which companies are keeping promises to stop deforestation in Indonesia for palm oil. Take a look now to see who’s keeping up – and who’s lagging way behind

The biggest forest fires of the century tore through Indonesia just six months ago. They reduced millions of hectares of of vibrant, living tropical rainforest and peatland to smoking ash – and with it, some of the last habitat of Indonesian orangutans.

A forest fire in Indonesia may seem like a far away issue, but for the past ten years, our investigations have exposed how the everyday products in our cupboards and on our bathroom shelves have direct links to the destruction of Indonesia’s rainforests.

For the average person, being a part of the solution isn’t as simple as making a few changes to your shopping habits. From Doritos to Colgate to Johnson & Johnson baby soap, palm oil is in so many products that it’s hard to avoid. Even if you could, palm oil isn’t the problem – deforestation is the problem, and that will only stop when corporations take responsibility for the palm oil they buy.

So when hundreds of thousands of Greenpeace supporters took action, they took the fight straight to the companies responsible. Using the power of mass pressure, one by one we began forcing the biggest brands that use palm oil or paper from Indonesia to promise to protect rainforests.

Then, a breakthrough. Two years ago, a host of massive brands – including Mars, Mondelez and Procter & Gamble committed to our campaign. Suddenly the biggest brands on the planet were all saying the same thing – that the destruction of these amazing forests had to stop.

And that’s not the end of the good news! This kind of collective action from corporations – with their immense purchasing power – puts huge pressure on traders and producers working directly on the ground. Companies like Wilmar International and Golden Agri Resources may not be household names, but they’re giants in the industry. And because of this they agree to end deforestation – an incredible result!

Now, the best part of a successful campaign like that is getting to see the real results: Protected forest, healthy orangutans, and an end to rampant deforestation and forest fires. That’s why we have to make sure the companies are keeping their promises.

So last December Greenpeace contacted 14 massive companies to find out how they were getting on with their commitments. What we found was a bit alarming. Only a few companies are making significant headway towards ensuring that there is no deforestation in their palm oil supply chains, and most are moving far too slowly.

It turns out, some companies might think that making a promise is easy – and that no one’s going to notice if they don’t keep it.

Cutting deforestation out of the palm oil supply chain http://www.scribd.com/doc/301773619/Cutting-deforestation-out-of-the-palm-oil-supply-chain

Out of all the companies we surveyed, Colgate-Palmolive, Johnson & Johnson and PepsiCo show the poorest performance and are failing to keep the ‘no deforestation’ promises they made to their customers. Tell them to up their game now

The truth is, we can’t afford to wait. Unbelievably, deforestation rates in Indonesia are actually increasing, instead of decreasing. And those huge fires from six months ago? They’re due to return in just a few months.

The palm oil industry is still a leading cause of all this destruction. And what’s even more frustrating is that palm oil can be produced responsibly. One amazing project we’ve been working with is a community in Dosan, Sumatra that is producing palm oil and protecting and restoring the surrounding rainforest. And there are lots of other schemes like this in Indonesia that need support.

It’s so important that these companies step up and deliver. Everyone knows what needs to happen, and how – so don’t let them get away with empty promises. Demand real change and real action on the ground.

What happen when you throw away plastic garbage

What really happens to your plastic when you throw it away?

Posted by David Wolfe on Wednesday, 29 April 2015

Saturday, 5 March 2016

Zero Waste Town

How This Japanese Town Produces No Trash

Posted by TestTube Video on Wednesday, 23 December 2015

Sunday, 28 February 2016

efficient living space

Jak by mělo/mohlo vypadat bydlení budoucnosti?

Posted by Prima ZOOM on Monday, 15 February 2016

Tuesday, 12 January 2016

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)